School budgeting is one part science and one part educated guesses seasoned with unforeseen circumstances and a pinch of hopeful thinking baked under a constant heat of state and federal requirements. Few of the key numbers are under school leaders’ control.

The Oregon Department of Education recalculates school districts’ State School Fund allotment right up to the biennium’s end. School boards won’t know for sure until the end of the 2027 fiscal year how much they actually have to spend in the budget they must approve by June 30 this year.

The Co-Chair Budget Framework estimate of $11.4 billion released this week gave school budget officials a better idea of what they will be working with but it’s no guarantee.

Even if the business officials guess the State School Fund exactly, they don’t know what they will receive. The State School Fund is a lump sum of local revenue like property taxes and state revenue divided up by adjusted enrollment numbers. If one district has significantly more or less students than projected, it not only affects their own allotment but also can alter the math on everyone’s share.

School districts get into problems, though, when a business official estimates wrong, and those problems come with compound interest the longer they go uncorrected. The Corbett School District east of Portland is paying the price now.

After hiring an in-house financial officer, Corbett discovered last summer that it was facing a $3 million deficit, roughly 20% of the budget. The district’s contracted outside accountant had been substantially overestimating expected revenues while substantially underestimating district costs for years, according to Superintendent Derek Fialkiewicz.

School budgets go through layers of public hearings, but their complexity makes problems hard to spot even for experts.

Corbett hired Regina Sampson in spring 2024, and she started attending budget meetings before she even started. She said she saw no red flags.

Even required audits won’t necessarily turn up problems because audits look at processes, not the actual numbers, Sampson said.

School districts receive monthly payments from the State School Fund based on enrollment, property tax payments based on collections and various grant payments based both on what they intend to spend and what they have already spent.

Expenses can vary based on labor negotiations, utility prices, staff changes or an unexpected facility problem.

Sampson said financial officers have to make a lot of educated guesses, but they need to have hard facts backing up estimates they present to superintendents.

“I have to be able to justify the things I’m doing,” she said.

Corbett is going a conservative route this year. Before the framework was released, Corbett started its budget based on an expectation of an $11.3 billion State School Fund. It will likely stick with that number.

Any change to a number means potentially hundreds of budget lines that must be changed, so business officials can’t realistically work up lots of scenarios. Typically, they have a best guess worked out line by line, with some areas where spending can be shifted if needed.

“I’d rather add than take away,” Fialkiewicz said.

But being conservative comes with a cost. Every fraction of a percentage point in a category is potentially someone’s job.

Sampson said the turmoil with the U.S. Department of Education, a significant source of school funding, is especially concerning because federal grants pay for things such as school-based mental health care and special education that the district can’t afford to maintain on its state funds.

“The ability to find those funds is not going to happen,” she said. “That’s jobs. We can’t pull that level of FTE into the general fund.”

Corbett has taken federal funds out of its projected budget because even an unexpected pause by the federal government would be crippling, Fialkiewicz said. Those federal grants are repayments for money already spent, and Corbett no longer has a reserve to carry it over if the paycheck doesn’t come.

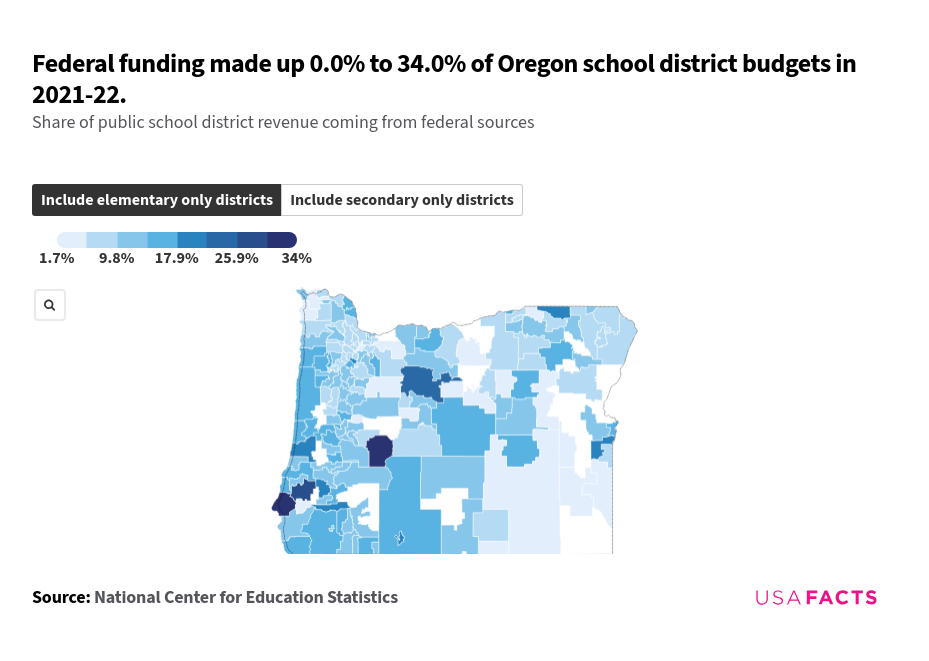

About 11% of Oregon public education funding comes from the federal government, according to USAFacts, a nonprofit, nonpartisan civic organization. That money flows to schools through the Oregon Department of Education and through direct grants, meaning the percentage varies by district.

School leaders don’t know how much of that money they can count on in the best of times, and districts are already seeing disruptions to grants they had counted on. The co-chair’s framework has scenarios for losses of up to 30% of federal funding.

With so much going on, Sampson said it is important for small districts to know they can reach out to the Oregon Association of School Business Officials for help. She said good accounting requires constantly reconciling the balance sheets as varying amounts flow into and out of all the necessary accounts, a high hurdle for districts too small for in-house accounting.

“For the really small districts, I don’t know how they do it,” she said.

It’s a constant battle.

School officials building budgets now based on hope for an $11.4 billion State School Fund have to keep one eye on the Legislature for unfunded mandates. New legislation that requires spending in specified areas can completely alter the budget landscape.

In 2024, for instance, the Legislature allowed school employees to collect unemployment in the summer, a big new expense for districts halfway through the budget cycle.

Jackie Olsen, Oregon Association of School Business Officials executive director, said budgeting is always a moving target.

“Every time you change one of those factors, you change the numbers,” Olsen said. “A budget is only right for one day.”

Even when the session ends, it’s still not a closed book. Districts receive monthly payments from ODE, but those payments can change as districts’ reported enrollment to ODE changes right up to the end of the biennium. Even if a district nails their enrollment perfectly, changes in the enrollment numbers of the larger districts can unexpectedly shift how much every school receives per student.

When districts come up short, the cuts can get painful quickly because roughly 85% of school costs go to staffing.

“There’s not a lot to cut,” said Olsen. “I can’t choose not to pay my electric bill.”

– Jake Arnold, OSBA

[email protected]

Part 1: Legislature writes $11.4 billion State School Fund in pencil