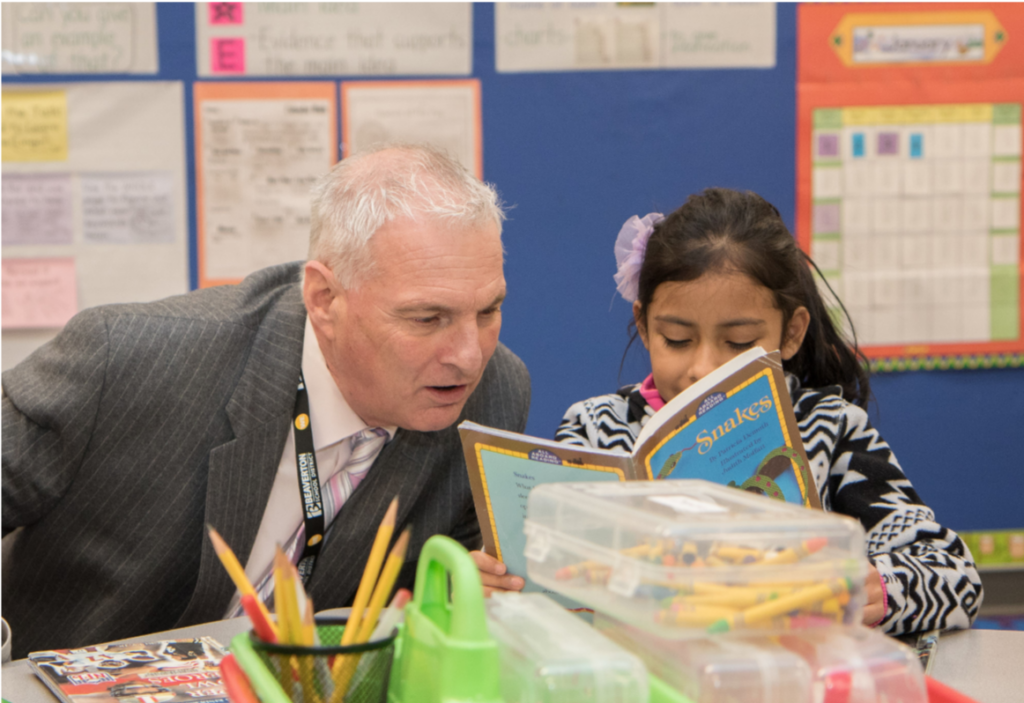

Beaverton Superintendent Don Grotting said the Student Success Act will push districts to take a hard look at whether their programs are making a difference for students. (Photo courtesy of Beaverton School District / 2016)

The Legislature has authorized roughly $500 million a year in new Student Investment Account grants, but legislators — and voters — will want to know what school districts are doing with that money.

As the Oregon Department of Education prepares regulations for 2020 Student Success Act implementation, superintendents are working out what the Student Investment Account transparency and accountability demands will mean for their districts.

Redmond School District Superintendent Michael McIntosh said his district began discussions before the session ended.

Districts are allowed four broad uses for the grants: increasing instructional time, addressing student health and safety needs, reducing class sizes and expanding well-rounded learning opportunities. Programs must meet students’ behavioral and mental health needs and increase academic achievement as well as reduce academic disparities among student groups.

“The class size reduction sounds good to us,” McIntosh said. He added that they want to add early elementary music and other coursework under well-rounded learning, tackle attendance issues, add 10 school days and increase the number of counselors.

The 2019 Student Success Act creates a new business tax to generate roughly $2 billion a biennium for education, with about half for early learning and statewide initiatives and the rest split among districts based on enrollment. The rules for tapping the funds are still being created, but some of the requirements for the Student Investment Accounts were laid out in the law.

Redmond won’t be able to do everything it wants with the roughly $6 million it expects from the Student Investment Account, but McIntosh said discussions with his school board will help set priorities and craft a vision.

McIntosh said the accountability requirements so far mostly fit with reporting the district already does and he hopes ODE doesn’t create a whole new system of reporting. He is wary of statewide rules, and he said he would love to see the state working with districts on an individual basis.

The Legislature invested ODE with oversight powers, but Deputy Superintendent of Public Instruction Colt Gill said he wants it to be a collaborative partnership, with ODE providing professional development and ongoing support.

“My philosophy here is that ODE shares responsibility for the success of each of our students with that local school, its district and its community,” Gill said.

Sen. Arnie Roblan, one of the Student Success Act’s creators, said legislators envisioned ODE as a support agency, not a compliance agency. Roblan said that when he was a teacher in the 1970s, ODE had expertise that teachers could call on. Federal education laws such as No Child Left Behind and the Every Student Succeeds Act have pushed the state agency into more of an oversight role.

Roblan, D-Coos Bay, said the act allows local control and decisions while encouraging ODE to help districts move toward best practices. The law includes a coaching program for struggling districts if they accept the money.

“We don’t have a hammer,” he said. “You have to buy into it.”

Districts must submit a four-year plan, to be updated every two years. The plan must be based on the district’s continuous improvement plan needs assessment, an academic impact analysis and budgets for the programs.

Roblan said the four-year plan forces program commitment but the two-year check-in allows districts to learn and adjust.

Districts must also answer to their communities. The act requires community input, school board approval and annual superintendent reports to the board.

OSBA will be working with the Confederation of Oregon School Administrators, the Oregon Education Association, representatives from communities of color and Hilltop Public Solutions consultants to help districts with their needs analysis, according to OSBA Executive Director Jim Green.

The Student Success Act emphasizes equity, and districts must engage communities that haven’t always been part of the conversation, Green said.

David Williams, Beaverton School District executive administrator for strategic relations, said the community’s view of its schools’ needs is as important as the district’s assessment. He said Beaverton might make a list of things it wants to do and call on the community to help identify the priorities.

Beaverton Superintendent Don Grotting said the process requires districts to take a hard look at their spending choices but he isn’t concerned about the accountability requirements.

“It’s maybe going to take a bit more planning time, but I believe that the Legislature went to bat for us, our governor went to bat for us, and they have really given us the best opportunity that Oregon children have had for long-term investments,” he said.

Beaverton has embraced data-driven program investments, and it was one of the early adopters of Forecast5, an OSBA-supported data-analysis application.

A scathing state audit of Portland Public Schools released in January called on legislators to examine how administrators were spending school money.

Scott Learn, principal auditor with the Secretary of State Audits Division, said the Student Success Act addressed some of the problems identified in the PPS audit. He said the Legislature had created a reasonable accountability framework with good measurement mechanisms.

ODE will review spending audits, help develop longitudinal performance growth targets and check districts’ progress annually. Learn said it will be important to see how legislators and ODE respond if districts don’t meet their targets.

“How sincerely are they going to really analyze the reasons why things aren’t being met and how much of it is going to be a public relations exercise in explaining it away?” Learn said.

The act identifies on-time graduation rate, five-year completion rate, ninth grade on-track rate, attendance and third-grade reading proficiency as benchmarks. Districts may also add their own metrics.

North Clackamas Assistant Superintendent Joel Stuart said the district expects to tie its requirements to their current key performance indicators, including third grade reading, eighth grade algebra readiness and 10th grade credit attainment.

Stuart said the district also values looking at the overall student experience through behavioral data, student surveys and community engagement. He said that although the act is designed to promote long-range planning, he expects to see system improvements after the first year.

ODE must report to the Legislature at the beginning of each year, and Gill said ODE shares responsibility with districts to make sure the Student Success Act gets results.

“This is Oregon’s largest investment in decades,” Gill said. “For most of us, this is a once-in-a-career opportunity to turn around outcomes for schools.”

ODE is working on the rules for grant applications for the 2020-21 school year, and it has pushed back its deadline for district continuous improvement plans to Nov. 1 so that districts have time to incorporate new requirements. Gill said the agency hopes to roll out the rules in January for a spring application period.

The Student Success Fund will dispense grants using the same formula as the State School Fund but with a double weight for students in poverty.

Over the next two years, ODE will add about 18 positions to monitor the Student Success Act, although some of those employees will have other responsibilities. ODE will create teams to help with district planning, to set up metrics guidelines and to manage grant distribution. ODE will also add two auditors.

A possible ballot challenge in January has cast a shadow over planning, though.

The Tigard-Tualatin School District is already laying the groundwork for defending the Student Success Act.

Superintendent Sue Rieke-Smith said district leaders recently went before the Westside Economic Alliance, a Washington County business group, to talk about the process for spending the money and how the district would be accountable.

Rieke-Smith said she asked that if business owners can’t support the act at the ballot to at least remain neutral so the district can do what it needs to do to educate their future workers. She said she invited them to be part of the process and promised to report back on the district’s work.

“If I’m asking you for $2 billion out of your bottom line, you need to know what I did with it,” she said.

– Jake Arnold, OSBA

[email protected]