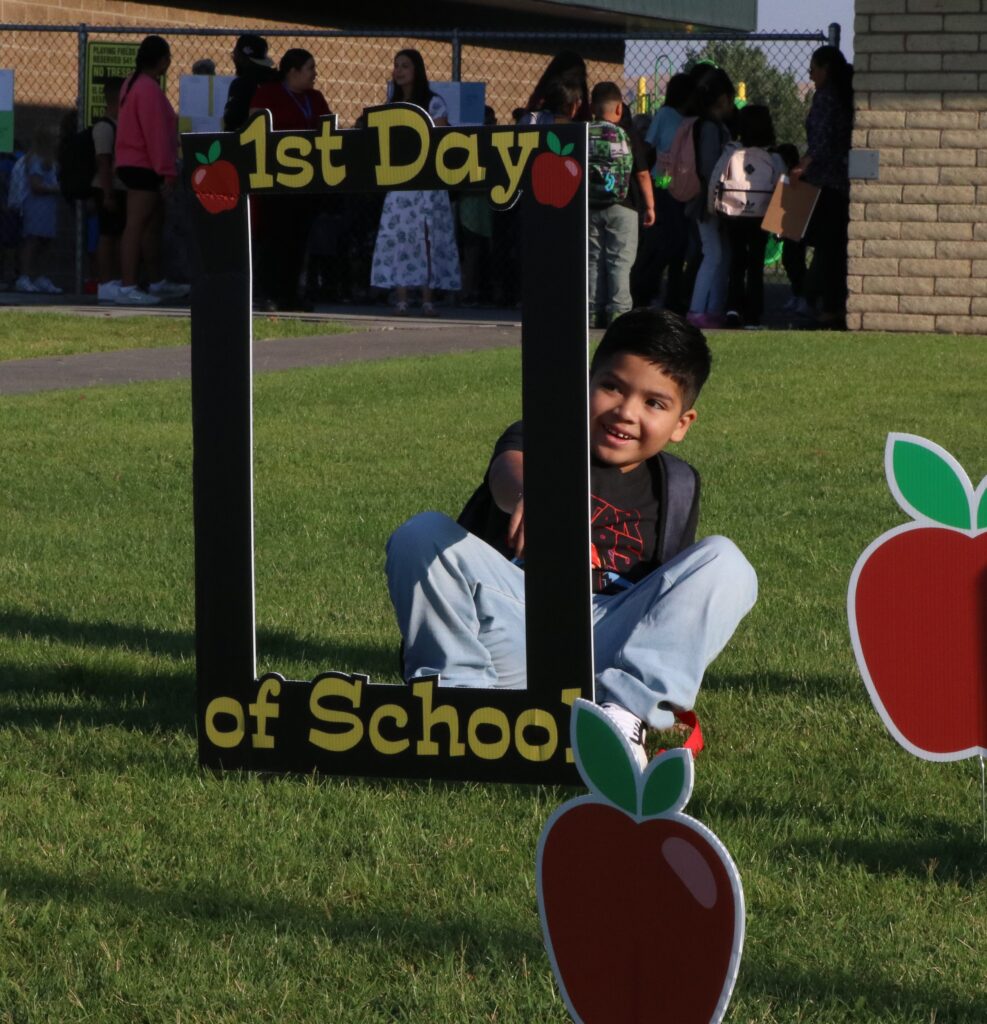

Second grader Andreas Zacarias is full of energy Monday, Aug. 28, the Umatilla School District’s first day. The new Umatilla Parents Club, which fosters community engagement with the schools, bought the signs for this year. (Photo by Jake Arnold, OSBA)

Umatilla School Board Chair Lesly Claustro-Sanguino kissed her twin second-graders goodbye on their first day of school Monday, Aug. 28. She watched as line after line of students in new shoes and favorite shirts followed their teachers into McNary Heights Elementary.

Claustro-Sanguino said it felt “surreal” to see her children enter the same school she attended, some of the same teachers still leading squads of children in the doors.

She notes her old school has changed, though, as it has renovated and reorganized to hold Umatilla’s soaring enrollment. While enrollment at most Oregon schools is falling, Umatilla is growing significantly. District and city leaders credit at least partially a responsiveness to area needs.

As public schools open their doors across the country this year, education leaders are nervously watching to see just how many students will walk through. U.S. public school enrollment dropped by more than 1 million in 2020 after COVID-19 closures drove students out of classrooms and didn’t go back up in 2021, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

In Oregon, enrollment dropped nearly 4% in 2020. Last February, the Oregon Department of Education reported enrollment fell for a third year in a row, although it had essentially leveled out with a decline of only 632 students out of more than 550,000. ODE will collect official data for this year based on Oct. 1 enrollment.

Umatilla and a smattering of other Oregon districts are seeing significant enrollment growth, though. Umatilla has nearly 1,500 students registered for this school year with kindergarteners still coming in, roughly 100 more than at the end of last school year, according to district data.

An area housing boom accompanying the arrival of Amazon data centers is certainly driving much of the growth in this town on the Columbia River near where it turns down from Washington. Umatilla, a community of around 7,500, has added 750 homes in the past four years, according to Mayor Caden Sipe.

Umatilla City Manager David Stockdale said the school district’s programs and services, though, are a selling point for people and businesses looking to relocate. He said diligent parents are discovering a district that responds to individual student requirements and works well with city and regional entities to create a welcoming environment.

Sipe, who is also a district teacher and the superintendent’s son, said newcomers already seeking cheaper housing or the eastern Oregon lifestyle tell him the schools are a draw.

Maria Sanchez, family liaison for the school district, said she is hearing the same thing from new families. Parents cite features such as the district’s small class sizes, robust after-school program and long-standing robotics program.

Umatilla’s fairly new dual-language program is what drew transfer parent Jacqueline Caldera. Nearly three-quarters of Umatilla students are Latino, and more than half its students speak English as a second language. Caldera said her daughter being able to converse with family members and read in Spanish filled her with pride.

On Monday, Caldera’s second grade daughter, Jazlynne, was just excited to see friends she hadn’t seen all summer. She is one of more than 100 students who live outside district boundaries.

Umatilla Superintendent Heidi Sipe said the district has a wait list for transfers so it can maintain its small class sizes. Classroom caps range from 18 in kindergarten to 30 for some high school classes. School funding is tied to enrollment, but Sipe said the district would not add students simply for the sake of growth.

School board member Jon Lorence said class sizes are a top district concern guiding transfer decisions.

“Students living in our district have to come first,” he said. “Even though we have growth, we have manageable numbers in our classroom.”

Like a lot of districts, Umatilla’s enrollment dropped during COVID, but it bounced back last year to roughly the same as before the pandemic. Sipe thinks maintaining supportive student services even when the students couldn’t be physically present fostered trust among families.

The building boom is raising average area incomes, but Umatilla has long been a high poverty school district, with all students eligible for free or reduced price lunches. Despite its demographic challenges, Umatilla regularly exceeds the state graduation average. For 2021-22, Umatilla had a 91% graduation rate while the state was 81%.

In 2016, area voters passed a district bond to create more room for an expected steady growth of students. McNary Heights turned custodial rooms into learning spaces and closets into staff offices and built new walls to create classrooms out of common areas.

“We utilize every space possible here for learning,” said Principal Nicole Coyle.

The boom has the district straining at the seams earlier than expected, though. To create a better learning environment for all, the district sought a bond in November. Stockdale called the overwhelming yes vote another indication of community approval of the district’s work.

Umatilla is planning an elementary school on land among the new housing springing up southwest of downtown. The district will redistribute its grade levels among its four buildings — with a K-3, 4-6, 7-8 and high school — to avoid having two elementary schools on opposite sides of town that could highlight economic disparities.

The district this summer expanded its day care space, a popular staff perk and a lifeline for teen parents trying to stay in school. The day care serves 27 children ranging in age from 6 weeks to five years old. Staff pay a monthly rate, but student parents can use the day care as drop-in whenever they need it.

Tammy Wagner, the day care operator, is a certified teacher. She is planning a career and technical education pathway for the roughly three dozen students who take her elective class while helping with the children.

On the first day’s sunny morning, though, surrounded by laughing children and proud parents awaiting the start of a new year, Claustro-Sanguino’s mind was on human development, not property development. She became a school board member before she even had children. She cares most about the students’ academic and social success.

“I want as much growth as possible for these kids,” she said.

– Jake Arnold, OSBA

[email protected]